Many writers talk about "digital natives" or describe these young people as "born digital." What do you see as the strength and limitations of these terms given what you found in your research?

Becky Herr: One potential strength of the term "digital generation" for describing young people and their relationship to technology is its acknowledgement that youth are using media and technology in interesting and important ways. Talking about kids as "digital natives" can be seen as a counterargument to pervasive discourses about kids as deviant users of technology--hackers, cheaters, wasters-of-time--or kids as victims of technology--the "prey" of online predators, for example. This is not to say that the term is used exclusively to describe positive interactions with technology; it also emphasizes the gap between the ways "digital natives" use technology and the ways non-natives (like adults) use technology.

What is worrying about the discourse of digital natives is that talking about young people as a "digital generation" risks romanticizing certain types of youth participation and ignoring important differences in access to media and technology, including barriers to access that are not tied to a lack of hardware--barriers like not reading and writing in English, being a girl and having to compete with boys in a classroom with limited resources, or parental rules borne out of moral panic. Further, the idea of a digital generation marked by shared characteristics (other than the dates of their birth) that outweigh other aspects of identity/subjectivity--race, class, gender, ability, (etc.) is problematic. What we have found in the Digital Youth project is that there is a huge amount of variation in the ways kids are using media and technology in their everyday lives. Yes, the ways in which these practices are enacted vary, often by peer group or by individual kid. We've also found that things like class, race, and gender continue to have significant influence in kids' lives.

In my own research, for example, I worked with kids at the middle school level who were using media production software (iMovie and PowerPoint) for the first time. At home, most of the students I observed and interviewed did not have a computer, Internet access, or any video equipment. However, they had other media and technology that was incredibly important to them and that they used in creative and sophisticated ways to find information, to express themselves, to communicate with friends, and to mess around in order to figure out things like game cheat codes or how to substitute a borrowed digital camera for an mp3 player. Some had vast music or DVD collections, others spent hours each day playing games on a video game console. Were they "digital natives"?

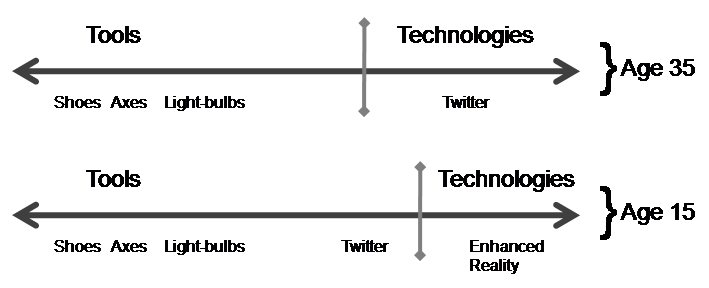

Christo Sims: There are also plenty of folks who weren't "born digital" who have developed incredible fluency in various forms of online participation. We also met numerous youth who weren't technically adept or comfortable participating online. By emphasizing a generational break we risk mystifying the factors that structure online participation, and equating competency automatically with age.

danah boyd: Many of those who use these terms often do so with the best of intentions, valorizing youth engagement with digital media to highlight the ways in which youth are not dumb, dependent, or incapable. Yet, by reinforcing distinctions between generations, we reinforce the endemic age segregation that is plaguing our society. Many social and civic ills stem from the ways that we separate people based on age. If we want to curtail bullying and increase political participation, we need to stop segmenting and segregating.

Parents and teachers often want to structure young people's time online. Yet your research suggests that some of the most productive experiences come when young people are "hanging out" or "messing around" with computers in relatively unstructured ways. Explain.

Mimi Ito: In a lot of our case studies, we saw examples of kids picking up media and technical literacy through social and recreational activity online. When they were given time and space to experiment, they often were able to pick up knowledge and skills through messing around, whether that was learning how to make a MySpace profile, experimenting with video, or figuring out how to use cheat codes in a game. Some kids used this kind of messing around as a jumping off point towards much more sophisticated forms of creative production or engagement with specialized knowledge communities.

Christo Sims: One story that comes to mind is a youth named Zelan who we feature in one of the sidebars in the Work chapter. Zelan comes from a very rural area where most of his peers will end up in working class jobs, doing construction, building roads, working as mechanics. Zelan, who identifies himself as a computer geek, leveraged his technical know-how for economic gain starting in junior high school: fixing electronics, buying and selling gaming and computer gear, and servicing the computers of neighbors and teachers. His passion, though, has been video games. He started as a player but soon became an enthusiast, subscribing to game magazines, following the latest releases, looking for tips online. In addition to becoming a fan he started messing around with broken consoles, taking them apart to see how they worked, trying to fix them so he could play a better console or sell it for a profit. He did all this without seeing it as leading towards a career or success in school. It was only once he started seeing that he his gaming interest was actually valuable to others at school and in the community that he began to imagine how these interests could lead to a life after high school. When I first met him he was a Junior and was thinking of starting a computer service business when he graduated. When I saw him again last summer he was headed to a technical college on scholarship.

Dan Perkel: Another person featured in one of the sidebars is Jacob. Jacob was an African American senior who had moved from the East Bay to Georgia and back again. Jacob, like others we talked to in our studies, joined MySpace when someone else made an account for him. For a while, Jacob didn't understand how to customize his page--again like other new members to the site--and had other people do it for him. On the friendship-driven side he used MySpace as a way to communicate with people he met and friends he left behind after various moves. However, at some point he made the connection between changing MySpace profiles and the web design classes that he had gotten into at school. He then took the time to better understand how to customize his own profile and consider making and distributing MySpace layouts, something he had seen others do on the site. When I last talked to him, he was considering a career in web design and said he had been offered a job already.

danah boyd: It is important to note that "productive" engagement doesn't necessarily mean only traditional learning or media and technical literacy. As a society, we've never spent much time considering how youth learn to be competent social beings, how they learn to make sense of cultural norms and develop social contracts, or how they learn to read others' reactions and act accordingly. We expect youth to be polite and tolerant, respect others' feelings, and behave appropriately in different situations. This is all learned. And it is not simply learned by telling kids to behave. They need to experiment socially, interact with peers, make mistakes and adjust. Stripping social interactions from youth's lives does not benefit them in any manner. I would argue that even the oft-demeaned social practices that take place online are extremely productive.

You write about "genres of participation." Explain this concept. What are the most important genres at the present time and why?

Mimi Ito: We use the concept of genre as a way of describing certain social and cultural patterns that are available and recognizable. Friendship-driven and interest-driven practices are based on genres that youth recognize, have particular practices associated with them, as well as certain kinds of identities. For example, interest-driven genres of participation tend to have a more geeky identity associated with them, involve congregating on specialized and often esoteric interests, and reaching beyond given, local school networks of friends. This is a whole package of things that goes together, a recognizable genre for how youth participate in online culture and social life. We also think of hanging out, messing around, and geeking out as genres of participation.

When and how might the borders between friendship-driven and interest-driven forms of engagement start to blur?

Mimi Ito: As with all genres, there are a lot of things that don't totally fit, and a lot of blurring between genres. When kids engage in friendship-driven practices, they often get involved in messing around with technology, and that can become a jumping off point for more interest driven activities. For example, some kids will begin messing around with video or photos that they take with their friends, and then they get more interested in the creative side of things. Conversely, we find that kids who connect to others around interests will often see these groups become really important friendship networks, and an alternative source of status and identity that is different from the mainstream of what happens in the school lunchroom.

You note throughout the report a broadening of who gets to "geek out" in today's youth culture. Explain. What factors are reshaping cultural attitudes towards "geek experiences"? Who gets to "geek out" now who didn't get to do so in the past?

Mimi Ito: Now that digital media and online networking has become so embedded in kids' everyday social and recreational lives, there is a certain baseline of technical engagement that is taken for granted. Only certain kids, though, decide to go from there to what we consider more geeked out kinds of practices. Predictably, it tends to be boys who geek out more than girls. Even though girls are often engaging in highly sophisticated forms of technology use and media creation, often they don't identify with it in a geeky way. What does seem to be changing though, is the overall accessibility that kids have to more geeked out practices because of the growing accessibility of digital media production tools as well as the ability to reach out to interest groups on the Internet. Although our study didn't really measure this, this may be particularly significant for less advantaged youth who would not otherwise have had access to specialized creative communities or media creation opportunities.

Patricia Lange: Being able to connect with dispersed networked publics enables kids to explore skills and receive mentoring that may be difficult to gain from co-located peers or teachers who do not have the same interests or experiences. For example, in my study of the video-making culture of YouTube, accessing mentors or assistance in a "just-in-time" fashion is inspiring and encouraging, especially given kids' decreasing ability to connect with other adults and potential mentors in neighborhoods and local communities. One of the things we heard very often was that friends, family, and kids at school often did not understand why young YouTubers wanted to "geek out" making videos. YouTube participants' school peers did not always have the same familiarity and expertise with how media is put together in ways that kids on YouTube did. Many of the kids we interviewed have already had extensive experiences making media. They often have very sophisticated visual literacies and complex ideologies about what makes a good or bad video, what constitutes appropriate participation in technical groups, and how they think about online safety. Failing to engage with these sites in school means there is no hands-on dialogue between teachers and students that might help shed light on why some kids thrive by geeking out and why others have difficulty.

You are using terms to describe these experiences which are much closer to those which might be used by young people than those deployed by parents and teachers. What are the implications of that shift in the terms of the discussion?

CJ Pascoe: In general we tried to take a Sociology of Youth approach to our findings in this book. In line with this approach we try to let the categories of analysis as well as the descriptive terms arise from the youth themselves, rather than imposing our adult categories on our findings. What this means is that we tried, for the most part to describe a social world from the point of view of its participants, rather than as (more powerful) outsiders. I think foregrounding our participants' terms, categories and experiences allowed us to challenge some of the common assumptions adults have about youth participation of new media.

Heather Horst: As is common in most ethnographic research, we integrate terms like 'hanging out', 'messing around' and 'geeking out' into our analysis in order to highlight the categories and perspectives that are meaningful to young people themselves. Throughout this project, we felt quite strongly that part of our role and responsibility as researchers as working to navigate the gaps between youth and adult-centered perspectives. While we recognize that this may involve some degree of translation work when talking to different audiences (e.g. educators, policy makers, etc.), if we really want to see changes in discussions about learning and education, youth voices and perspectives need to be brought to the table.

danah boyd is a doctoral candidate in the School of Information at the University of California, Berkeley and a Fellow at the Harvard University Law School Berkman Center for Internet and Society. Her research focuses on how American youth engage in networked publics such as MySpace, YouTube, Facebook, Xanga, etc. She is interested in how teens formulate a presentation of self and negotiate socialization in mediated contexts with invisible audiences. In addition to her research, danah works with a wide variety of companies and is an active blogger.

Becky Herr-Stephenson is an Associate Specialist at the University of California Humanities Research Institute at UC Irvine. Becky's research interests include media literacy, teaching and learning with popular culture, and youth media production. Her dissertation, "Kids as Cultural Producers: Consumption, Literacy, and Participation," investigates issues of access and media literacy through an ethnographic study of media production projects in two mixed-grade (sixth, seventh, and eighth) special education classes. Previously, she was a member of the research team for the Digital Youth Project and a graduate fellow at the Annenberg Center for Communication. Before beginning her graduate studies, Becky worked as a production manager for companies producing original content for the web and multimedia museum exhibits. Her current work with the DMLstudio involves a literature review of institutional efforts related to youth digital media production. Becky recently completed her PhD in Communication at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Southern California.

Heather Horst is an Associate Project Scientist at the University of California, Irvine (UCHRI) who conducted research during the Digital Youth Project as a Postdoctoral Scholar at University of California, Berkeley. Heather is a sociocultural anthropologist by training who is interested in the materiality of place, space, and new information and communication technologies. Before joining the Digital Youth Project in 2005, she carried out research on conceptions of home among Jamaican transnational migrants, as well as issues of digital inequality, as part of a large-scale DFID-funded project titled "Information Society: Emergent Technologies and Development in the South," which compared the relationship between ICTs and development in Ghana, India, Jamaica, and South Africa. Her coauthored book with Daniel Miller, The Cell Phone: An Anthropology of Communication (Oxford, UK, and New York: Berg, 2006), was the first ethnography of mobile phones in the developing world. Heather's research in the Digital Youth Project integrates her interest in media and technology in domestic spaces, families in Silicon Valley, and the economic lives of kids on sites such as Neopets.

Patricia G. Lange is a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for Multimedia Literacy at the University of Southern California. She received her PhD in Anthropology from the University of Michigan. Her areas of interest for the Digital Youth Project are centered around using theories from anthropology and linguistics to understand the cultural dynamics of video creation, reception, and exchange among kids and youth. She is studying YouTube as well as video blogging groups to gain insight into the cultural aspects of video sharing and how these practices change ideas about the public and private. Lange is exploring how the content and form of videos as well as material video sharing and response practices serve as sites of identity negotiation, emotional expression, and promotion of public discourse in increasingly video-mediated, online milieu. She has recently published articles in a variety of journals including: Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, Discourse Studies, Anthropology of Work Review, First Monday, and The Scholar and Feminist Online.

Mizuko (Mimi) Ito is a cultural anthropologist specializing in media technology use by children and youth. She holds an MA in Anthropology, a PhD in Education and a PhD in Anthropology from Stanford University. Ito has studied a wide range of digitally augmented social practices, including online gaming and social communities, the production and consumption of children's software, play with children's new media, mobile phone use in Japan, and an undergraduate multimedia-based curriculum. Her current work focuses on Japanese technoculture, and for the Digital Youth Project she is researching English-language fandoms surrounding Japanese popular culture.

C.J. Pascoe is a sociologist who is interested in sexuality, gender, youth, and new media. Her book on gender in high school, Dude, You're a Fag: Masculinity and Sexuality in High School, recently received the 2008 Outstanding Book Award from the American Educational Research Association. As a researcher with the Digital Youth Project she researched the role of new media in teens' dating and romance practices. Her project "Living Digital" examines how teenagers navigate digital technology and how new media have become a central part of contemporary teen culture with a particular focus on teens' courtship, romance, and intimacy practices. Along with Dr. Natalie Boero she conducted a study titled "No Wannarexics Allowed," looking at the formation of online pro-anorexia communities and focusing on gender, sexuality, and embodiment online. C.J. is currently an Assistant Professor of Sociology at The Colorado College.

Dan Perkel is a PhD candidate at UC Berkeley's School of Information. His research explores how young people use the web and other technologies as a part of their everyday media production activities. Dan's ongoing dissertation research investigates the mutual shaping of young people's creative practices and the social and technical infrastructure that support them. Prior projects include explorations into the design of a collaborative storytelling environment for fifth-graders, ethnographic inquiry into an after-school media and technology program, and investigations using diary studies to capture everyday technology use. With UC Berkeley artist Greg Niemeyer and colleague Ryan Shaw, Dan helped create an art installation called Organum, which looks at collaborative game play using the human voice (and which was followed up by "Good Morning Flowers"). In a past life, Dan worked as an interface designer, product manager, and implementations director for Hive Group, whose Honeycomb software helps people make decisions through data visualization. He received his BA (2000) in Science, Technology, and Society from Stanford University, graduating Phi Beta Kappa, and his Master's in Information Management and Systems from UC Berkeley's School of Information in 2005.

Christo Sims is a PhD student at UC Berkeley's School of Information. He was a member of the Digital Youth research team from 2005 until 2008. His fieldwork focused on the ways youth use new media in everyday social practices involving friends, family, and intimates. He conducted research at two sites, one in rural Northern California, the other in Brooklyn, New York. His contributions can mostly be found in the report's chapters on Intimacy, Friendship, and Families. Christo received his Master's degree from UC Berkeley's School of Information in the spring of 2007, and his Bachelor's degree from Bowdoin College in the spring of 2000.