So, after ten weeks of speaking and traveling across Europe, my wife and I have finally return to Los Angeles, more than a little road weary and jet-lagged, but eager to share some of the new contacts and insights I've gained through my travel. I hope to share some of my travel experiences before much longer, but in the meantime, I am trying to catch up with a range of other things which have happened since I have been away.

Today, I wanted to share with you an article which I wrote about the 2011 San Diego Comic-Con for Boom: A Journal of California, which has finally come out in print -- just in time for Comic-Con 2012. I am not in San Diego this week -- it would have been too much to tackle after my long trip -- but half the people I know are there, so I figured I would prioritize sharing this article with my regular readers. If you would like to read a PDF of the article as it appears in the magazine, including a range of eye-catching photographs, you can find it here:

And you can find the issue itself on the newstand, where-ever quality publications like Boom may be sold in your community.

"Super-Powered Fans": The Many Worlds of San Diego Comic-Con

by Henry Jenkins, written for Boom: A Journal of California

In an "Only at..." moment, the New German Cinema auteur Werner Herzog made a surprise appearance at the 2011 Comic-Con International event. Popping up during a panel focused on the Discovery Channel's Dinosaur Revolution series, Herzog pontificated in a Bavarian accent about how the four-day geekfest represented an epic acting out of the public's "collective dreams." We all applauded with delight as Herzog, known for his art films and documentaries, bubbled with boyish enthusiasm about fandom's ritual practices and shared beliefs as breathlessly as he might have talked about going up the Amazon River to film Fitzcaraldo, or in search of prehistoric art for his more recent Cave of Forgotten Dreams.

A few years ago, another documentary filmmaker, Morgan Spurlock, found himself in conversation with comic book legend Stan Lee at one of Comic-Con's cocktail parties. The pair got excited about possibilities for documenting the festivities. Spurlock's agent connected him to another client in attendance, Firefly mastermind Joss Whedon. Soon, famed blogger Harry Knowles (Ain't It Cool News), also in San Diego for the conference, had joined the dialogue. The team shot a film (Comic-Con Episode IV: A Fan's Hope) at the 2010 convention, and it started playing on the film festival circuit in the fall of 2011. Further, a photo book based on the documentary was selling on the Comic-Con exhibit floor in 2011 with the tagline, "See anyone you know?" For more and more of us, the answer is hell yes! (For the record, mine is one of hundreds of snapshots on the book's cover.)

If you have a single geeky bone in your body (and who doesn't these days?), you have probably heard about Comic-Con, which is held each year at the San Diego Convention Center. Entertainment Weekly does an annual Comic-Con cover story. The Los Angeles Times does a special insert. And trade publications like The Hollywood Reporter also provide extensive coverage. However, for the most part, these reporters rarely get outside Hall H (where most of the film-related programming is held) or Ballroom 20 (where the high-profile television events take place). Mainstream journalists are focused on what the big studios and A-list celebrities are doing. If they do get beyond that, they typically focus on the spectacular costumes. Both are part of what makes this gathering so interesting, but there's much more to the Comic-Con story.

Comic-Con has a history, culture, economy and politics all its own, one we can only understand if we go beyond the celebrities, spoilers, and costumes and explore some of

the many different functions the con performs for the diverse groups that gather there. Comic-Con International is press junket, trade show, collector's mart, public forum, academic conference, and arts festival, all in one.

I have been active in this world for almost three decades. Students who take my classes about comics, games, transmedia entertainment, and science fiction have sometimes called me a professor of "Comic-Con Studies." But, compared to those who have been attending the Con for four decades, I'm still a relative newcomer; the 2011 festival was only my fourth time at the event.

I came to Comic-Con, first and foremost, as a fan--wanting, like everyone else, to see the artists who create the pop culture fantasies I love. By my second year, I was there as an academic, speaking as part of the event's track of scholarly programming and as part of a larger movement to legitimatize "comic studies" as an emerging field. By the third year, I was asked to participate in industry panels, reflecting the degree to which my research on fan cultures and transmedia entertainment has attracted interest from Hollywood. And last year I was there as an embedded journalist or native guide (pick your favorite metaphor), intending to help Boom's readers understand what Comic-Con was all about.

Comic-Con is the center of the trends I describe in my book Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. It's the meeting point between a transmedia commercial culture and a grassroots participatory culture, the place where an uncertain Hollywood goes when it wants to better understand its always unstable relations with its audiences. Comic-Con is a gathering of the tribes, a crossroads for many different communities drawn together by their shared love of popular mythology. What follows are a series of snapshots of the many different Comic-Cons, all functioning inside the San Diego Convention Center every year, simultaneously. Each of these vignettes from Comic-Con 2011 tells us something about how we produce and engage with entertainment media in a networked culture.

Comic-Con as Invasion

Organizers estimated that almost 140,000 people attended the 2011 event. To put this into some perspective, that's just a little under the population of Pasadena (147k) or, perhaps more to the point, of Hollywood (146k). Read through a different lens, Comic-Con attendance figures equal roughly half the number of people the federal government estimates have full or part-time employment in the motion picture industry. And Comic-Con's population is roughly one tenth of the population of San Diego itself.

For those five days, fans own the San Diego Convention Center, whose futuristic architecture--all pristine white and glistening metal--mirrors some cheesy 1970s-era science fiction flick (say, Logan's Run). More than that, the fans own downtown San Diego. Imagine this San Diego scene I saw unfold last year: The landscape is dotted with giant inflatable Smurfs, a full-scale reconstruction of South Park, and a building wrapped in Batman promotional material. The 7-Eleven in front of me has posters depicting Steampunk versions of Slurpee machines, courtesy of Cowboys and Aliens. Over there, sitting at a table outside the Spaghetti Factory, are Batman and Wolverine, united by a shared taste for black leather--never mind that they come from fundamentally different universes ("You're from DC; I'm from Marvel"). An armada of Pedi-cabs are passing by, ferrying fans anywhere they want to go. One of the cabs you see pass is a replica of the throne from Game of Thrones (a project from HBO which soon took on mythic status at the event, as I repeatedly heard people say, "Did you see...?" and "Did you hear about...?").

As I walk ahead, every congestion point in the foot traffic, such as the crossing of the trolley tracks, has been transformed into a gathering place for marketers trying to pass out swag and fliers. As we approach the convention center, we are accosted by Ninja Turtles and Captain Americas, by sexy booth babes in fur bikinis, and--perhaps most effectively--by a bevy of retro Pan Am stewardesses giving away vintage-style powder blue flight bags and walking in unison, having mastered the wave and the twirl with stylized femininity.

Comic-Con as Homecoming Party

Science fiction and comics fans have been holding gatherings at least since the first World Science Fiction Convention in 1939 (an ambitious name for a group which at the time probably didn't draw many from outside the Brooklyn area). Some cons are focused around a single media property--historically Star Trek or Star Wars, these days more often Harry Potter. Others are focused on a genre, such as comic books or anime or role-playing games. Many people at Comic-Con attend these other, more specialized, more local gatherings throughout the year, but they all come home to San Diego. Thus, Comic-Con has become the Mega-con, the Con to end all Cons, the gathering place for fans of all varieties (and yes, now, from all over the planet).

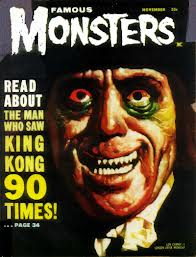

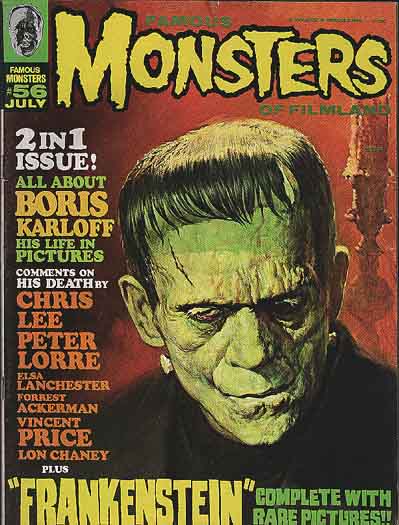

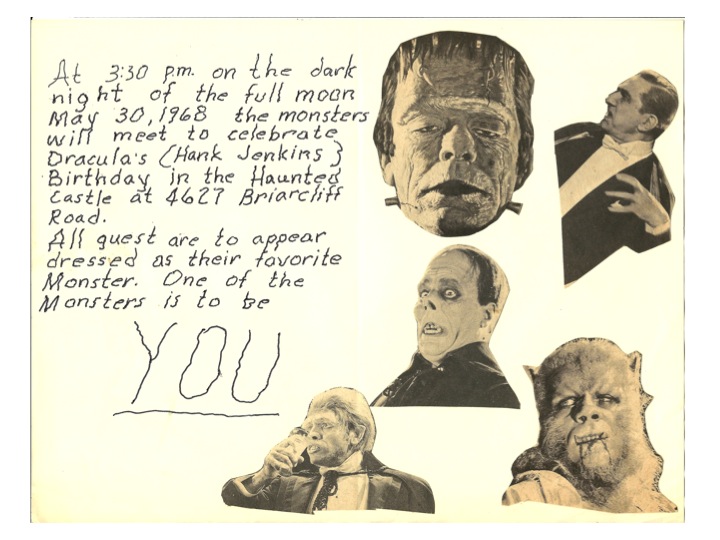

Comic-Con started as a small regional comics convention in 1970 with 170 attendees. The organizers sought to broaden their base by including other related interests, including the Society for Creative Anachronisms, The Mythopoetic Society, and, later, gamers and anime fans. By 1980, the convention attracted 5,000 attendees. This was the heyday of comics collecting, when vintage comics discovered in old attics were being avidly sought by wealthy adult collectors. The comics "bubble" eventually popped: vintage comics were valuable because so many mothers had thrown them away, creating artificial scarcity. But by then, genre entertainment had moved from B movies and midnight movies to major Hollywood summer blockbuster status, and the Con kept undergoing growth spurts--15,000 in 1990; 48,000 in 2000; and 130,000 in 2010.The Con so swamped the available hotel rooms in 2011 that my wife and I ended up renting a dorm room at a local college miles away, spending the five days of our stay sleeping in cramped bunk beds.

Today, one of my big ambivalences about Comic-Con is how much it now emphasizes fans as consumers rather than fans as cultural producers. There's a small alleyway tucked in the back corners where fan clubs have booths to attract new members. There are panels where fan podcasts are being recorded, where fan fiction is being discussed, and where costumers trade tips with each other. For the most part, however, Comic-Con International puts the professionals in the center and the subcultural activities the conference was based on at the fringes.

Comic-Con as Publicity Event

Today's television has moved from an appointment-based medium where viewers watch programs at scheduled times to an engagement-based medium where people seek out content through many different media (from Hulu and iTunes to boxed sets of Dvds) on their own time and as their interests dictate. Today's Comic-Con is shaped by the idea of the fan not as a collector, but as an influencer. Most Comic-Con attendees are "early adopters" of communication technologies; they have blogs, Facebook pages, Twitter accounts, etc., and know how to use them. These fans have become the leading edge of the studio's promotional campaigns. Industry research shows that Twitter hashtags represent one of the best predictors of box office success, both because the kinds of folks who see movies on the opening weekend are more often likely to be the type to tweet about their activities, and because these grassroots intermediaries help to inform and shape the ticket-buying habits of more casual audience members.

San Diego seems to be the right place--just close enough to Los Angeles to draw A-list celebrities, just far enough that it makes for a great road trip for those feeling claustrophobic in the media capital. And it's the right time, in the midst of the summer movie madness and less than a month before the launch of the fall television season, to draw maximum attention from the media industry. This is the one time of the year when many Hollywood types directly interface with their audiences, and probably the only place where they are doing so on the fans' terms. Their mission is to "break through the clutter."

Ironically, of course, Comic-Con is perhaps the most media saturated environment you can imagine! Hollywood studios and television networks have to pull out all stops if they want to play, from clips of previously unreleased footage or surprise appearances by crowd-pleasing celebrities to displays of costumes, props, and sets on the floor of Exhibit Hall. In 2010, Marvel introduced the entire cast of the forthcoming Avengers film. In 2011, Andrew Garfield, the new Spider-Man, created a stir--making his grand entrance wearing a "Spidey" Halloween costume, pretending to be a fan asking a question from the floor mic.

My family, like many fans, prepare for Comic-Con as if it were a military operation. By the time we get there, we've mapped and charted our priorities. We know what we most want to see. And we have strategies for the best way to get into the highly attended event. You usually have to awaken and get in line hours early or, more risky, find a point in the schedule which is not a big draw to grab a seat and hold it through a parade of lower-profile panels. The organizers don't "flush" the theater between events, so you can defend your squatting rights. In Ballroom 20, at least, you can get a bathroom pass and come back in without waiting in line.

These practices have their downsides and upsides. Some events draw apathetic and distracted audiences while the true blue fans are locked outside. But attendees get exposed to media properties they might not otherwise encounter. This gives producers who are still struggling to find their audience a unique opportunity to win over new viewers. We lined up outside Ballroom 20, with the primary goal of seeing the Game of Thrones panel, and sat through Burn Notice, Covert Affairs, and Psyche sessions. And it's a good thing we did; more than 7,000 people were turned away from the Game of Thrones panel, presenting at Comic-Con for the first time this year.

A few years ago, the conference organizers were discouraging fans from tweeting about what they heard. Today, exclusivity and secrecy have given way to publicity. Now, Comic-Con's organizers are announcing hashtags (words or phrases preceded by # that allow Twitter users to find others talking about the same topics) in front of every panel. Many speakers are recruiting Twitter followers. And some networks are collaborating with Foursquare, all sure signs the "fan as influencer" paradigm is shaping their branding strategies. We were warned again and again not to tape the clips shown, but, this year, most of them got released in good quality formats to the leading science fiction blogs within days, if not hours, after the event.

Comic-Con as Jury

The myth, at least partially true, was that Comic-Con was key to the early success of such cult television series as Heroes, Lost, True Blood, and The Walking Dead, and that it also crushed the hopes of misguided movie efforts, such as Catwoman and Ang Lee's Hulk, both dead on arrival after negative Comic-Con response. However, Hollywood's fascination with the Comic-Con "bounce" has been deflated by the mediocre box office of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, Tron, and Sucker Punch, huge buzz-makers at 2010 Comic-Con that failed to deliver months later. In response, some major studios (Warner Bros, Marvel, Disney, Dream Works and The Weinstein Company) opted not to present at the 2011 convention. By then, the prevailing wisdom was that Comic-Con fans will turn out opening weekend for the superhero blockbusters with or without big promotion at the event. On the other hand, genre television programs such as Grimm, Once Upon a Time, Alcatraz, Terra Nova, and Person of Interest require highly engaged viewers to draw in their friends and families week after week. And, in film, the real beneficiaries of Comic-Con have been lower budget, slightly off-beat, and smart genre films, such as District Nine, Monsters, Moon, Paul, or Attack The Block, few of which have been "hits" but most of which might not make it into the multiplex without Comic-Con mojo. In any case, the news that Hollywood was stepping back from Comic-Con turned out to be overstated; 2011 speakers included Steven Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola, Kevin Smith, Guillermo Del Toro, Jon Favreau, Peter Jackson, and, yes, Werner Herzog.

Normally, I am exhausted by the time late afternoon comes at Comic-Con. The sensory bombardment (the buzz and crackle of massive television monitors, the smell of over-priced hotdogs and nachos, the constant shock of random encounters with people dressed like their favorite cartoon characters) is simply too intense to prolong. Having gotten up at the crack of dawn to wait in line for some high-profile event, by late afternoon parents are getting into red-faced fights with their children, couples seem to be in danger of breaking up, and people are slumped over on the buses, some snoring, others weeping, from the exhaustion.

We stayed late on Friday, hoping to get into a packed hall to watch the pilot of a television series, Locke and Key--a pilot which most fans knew in all likelihood would never reach the air. Fox commissioned this series based on the best-selling horror comics from Steven King's son, Joe Hill, who was recognized that weekend by the Eisner Awards as the best comics writer of the year. Fox decided not to add Locke and Key to their slate. The producers shared the pilot here in hopes of rallying fan support behind either airing it on another network or developing it straight-to-DVD. The pilot was remarkably faithful to the original graphic novel and respected the intelligence of comic book fans. (No wonder Fox didn't pick it up!) But the producer's efforts to rally fan support suggests just how much weight they believe this jury might play in shaping the fate of cult media properties.

By contrast, Grimm, a fairy-tale themed series that made it onto NBC's fall line-up, had trouble finding the love, despite a pedigree that includes top writers from Angel. The Comic-Con crowd snorted over one obvious plot device (a woman who keeps passing out every time she's about to deliver a key piece of information) and rustled their feet over abrupt shifts in tone and style. As my wife put it, Grimm "doesn't know what it wants to be when it grows up." Some fans were already skeptical going into this event because Grimm and Once Upon a Time, both on the fall schedule, seemed so clearly derivative of a long-run Vertigo comics series, Fables. All of them explored the fantasy of storyland characters entering our contemporary reality.

Fans applauded politely when the lights rose, but everyone there knew this screening was, well, grim. (Grimm was picked up for a full season, but its ratings have been lackluster compared to the success of its rival, Once Upon a Time.) Contrary to what some producers might have told themselves, the Comic-Con crowd isn't fickle: it knows exactly what it wants from genre entertainment, and the producers had better deliver it or face our collective scorn.

Comic-Con as Consciousness-Raising Session

The popular vampire series Twilight's stars and producers opened the film program in 2011. Twilight's involvement in Comic-Con has been controversial, with picketers marching outside the theater in years past with signs proclaiming that "real vampires don't sparkle" and "Twi-hards, go home." Throughout the first half of the 20th century, science fiction and comics fandom were dominated by technologically inclined men. However, by the early 1960s, feminist writers like Ursula K. Le Guin or Joanna Russ were drawing more women to fan gatherings, and there have been high-profile conflicts around gender in fandom ever since. Go to some cons, and the attendees are overwhelmingly male. Others are overwhelmingly female. Comic-Con (in recent years at least) has felt a dramatic increase in female attendance that has brought with it some growing pains. The same year that a small number of male fans picketed the Twilight panel, for instance, people were passing out fliers about sexual harassment, suggesting uncertainty about how the fanboys and fangirls were going to interact.

In fact, there were huge numbers of female fans in line outside Ballroom 20--not teenyboppers wanting to hamster-pile Robert Pattison, not girlfriends of male fans, and not exhibitionists trying to see how much skin they could show (all stereotypes of female fans fostered by the news media). These were dedicated fans in their own right, pursuing their own desires and interests. And, by all reports, male fans this year were more worked up over DC's decision to re-launch and renumber all of their titles than about the presence or absence of Twilight fangirls. Comic-Con is featuring more and more women in its programming (including female producers and showrunners who are starting to impact genre entertainment), and they are often peppered by questions about how to survive in an industry still largely dominated by men.

Some have argued that Hollywood's discovery of Comic-Con has inspired the "rise of the fanboy" as a powerful influence on production decisions. The gendered language is purposeful since, apart from the Twilight conflicts, producers and journalists don't seem to have noticed that there are women gathering in San Diego now, too. How long before their tastes and interests become part of the equation, as the media industry seeks to court their most passionate and influential fans?

And something similar is starting to happen around race and ethnicity. Most fan gatherings are heavily Caucasian, while the few minorities in attendance gather by themselves on panels focused on why fandom is "so damn white." But, perhaps as a result of the Southern California location, Comic-Con is by far the most racially and ethnically diverse fan gathering in the country. If San Diego is where Hollywood sends its people to learn what the audience thinks, they encounter a multi-racial mix, often with strong views about the ways minorities get marginalized or stereotyped in popular media. In some ways, genre franchises, such as Lost, Heroes, The Matrix, and Star Trek have done a much better job including people of color than other genres. But they still lag behind an American population that is increasingly becoming a minority majority.

At a panel I attended on diversity and fandom, there was lots of discussion about the Racebending campaign launched by fans of The Last Airbender. These fans protested Hollywood's efforts to take an animated series known for its multicultural representations and make it into a live-action film with white actors cast in most major roles. The fans pushed back, using their online communication skills and partnering with traditional activist groups such as Media Action Network for Asian Americans, to educate their community about the history of "white-casting." They weren't successful at changing the casting decisions, but much of The Last Airbender coverage mentioned their protest, and there are many signs that Hollywood is now running gun-shy, backing off other recent casting decisions (Runaways, Akira) when fans and industry critics, including George Takai, call them out. Fans now represent an important force pushing the industry toward a fuller representation of what America looks like--fans as influencers in a different sense.

Comic-Con as Costume Party

If you've seen a photograph of Comic-Con, odds are that it showed some fan in a costume. Keep in mind that most of us don't dress up (or strip down) for the con. However, for those who do, seeing and being seen at Comic-Con is a big part of the fun.

Why do so many people wear costumes at Comic-Con? For the same reason people dress up in costumes at Carnival in Rio, Mardi Gras in New Orleans, Burning Man in the Black Rock Desert. For that matter, why did you dress up for the office Halloween party last year? Because wearing red, blue, or green spandex frees us from what fans like to call our "mundane" roles and creates a festive environment. Herzog nailed it. Comic-Con is a field of dreams and wearing costumes transforms those "dreams" from something personal and private to something shared and public. Showing a pudgy midriff or pasty white skin amidst fur and feathers allows nerds (typically defined by their brains and not their bodies) to feel sexy. Donning cape and cowl allows children and adults to play together, strangers to find others with the same values, and fans to become micro-celebrities posing for pictures with other guests.

Watching all of these costumed characters creates a kind of intertextual vertigo; the more fanlore you know, the more you take pleasure in seeing incongruous juxtapositions. One of my favorite sightings of the weekend was a bevy of women dressed as Disney princesses ordering Bloody Marys at a mock-up of Fangtasia, the vampire bar from HBO's True Blood. And there were periodic meet-ups where characters from the same universes came together--twenty or so Princess Leia slave girls, an assembly of the Avengers which included someone dressed as Marvel mastermind Stan Lee, and a parade of characters from He-Man and the Masters of the Universe. Out on the streets, I even witnessed a chance encounter between a woman wearing a skin-tight bright blue latex Mystique costume (X-Men) chatting with an equally blue Na'vi from James Cameron's Avatar, suggesting their common identities as, pardon the pun, people of color.

In Japan, they call it cosplay, andevery weekend there are meet-ups of genre-themed cosplayers in Tokyo's YoYoGi Park. But the scope, scale, and diversity of what you can see here supersedes anything that's ever gone down at Harajuku Station.

Comic-Con as Networking Event

A high percentage of Hollywood insiders have emerged from the ranks of fandom. Kevin Smith, Guillermo Del Toro, Joss Whedon, and J. J. Abrams come back year after year because fans accept them as "one of us." Historically, most major science fiction writers published their first works in amateur fanzines. More and more stars and creators of cult films and television series have similar histories and would come to Comic-Con even if they weren't paid. Darren Criss, Glee's hot-stuff Blaine, was making YouTube videos performing Harry Potter songs only a year or two before joining the show.

Because they are all in San Diego for the weekend, industry insiders use the event to do what they do best--pass around business cards, buy each other lunch, and otherwise network. For the industry insiders and wannabes, the challenge is how to "dress for success" in this festive environment, how to hold onto professional standards while looking like you belong and are not simply a Comic-Con poseur, there just to cut deals. Of course, the other challenge is figuring out how to schedule business meetings so they don't conflict with the Doctor Who panel you really want to attend.

There's no question that Comic-Con represents a different kind of trade show environment for corporate networking. If you go to E3, say, you mostly end up talking to other game designers; at ShoWest, movie people; at the National Association of Broadcasters, television folks. But Comic-Con draws from all of the entertainment sectors. Thus, Comic-Con has become the common ground where transmedia deals get cut, yet another reason why it has gained greater importance in an era of media convergence.

Comic-Con as Marketplace

Sooner or later, everyone ends up in the Exhibit Hall, typically multiple times over the weekend. Sometimes it feels like all or most of the 140,000 attendees end up there at the same time. As one fan put it, Comic-Con is the closest thing to Christmas morning you are going to experience as an adult. Again, most media coverage highlights items which fit a mainstream conception of geek culture--ice trays which depict Han Solo in carbonite or sleeping bags which look like the inside of a Tauntaun (both of which, I admit, are pretty cool). But, if you noticed hipsters walking the streets of San Francisco or Los Angles in the fall dressed like contemporary versions of Peter Pan's Lost Boys in big furry hoods, it might be because they got such media attention at San Diego that summer. And Exhibit Hall is where all of the different communities can find "the stuff dreams are made of"--the otaku (fans of Japanese-made media); the connoisseurs of high-priced original comic book and animation art; the collectors of vintage toys and high-end action figures; the dealers in autographs; the furries (whose kink is dressing up like anthropomorphic animals). Many of these interests are so particular and so dispersed that it's hard to find what you're looking for in any given city. Perhaps you can track stuff down on eBay or Etsy, but many hope that it is all at Comic-Con.

For example, my tastes increasingly run toward retrofuturism, a fascination with older imaginings of the future. Steampunk represents one form of retrofuturism and is to Victorian science fiction what Goth is to Victorian fantasy and horror. Steampunk builds outward from the imaginings of Jules Verne and his contemporaries, constructing a technological realm which never existed, built with brass, stained glass, and mahogany. The Exhibit Hall offered everything from handcrafted lab equipment and goggles to high-end steampunk weapons (created by WETA, the New Zealand special effects house responsible for the Lord of the Rings movies.)

In a related vein, I dig mid-century modern images inspired by the "World of Tomorrow" offering at the 1939 World's Fair. I was especially drawn to booths which dealt with "paper"--old posters, comic strip pages, and other printed matter from the early part of the 20th century. More generally, I collect older forms of media--magic lanterns, stereoscopes, and the like. Somewhere in between lies a new project which has captured my imagination--the production and distribution of new low-fi music on old Victrola wax cylinders. Science fiction fans are increasingly drawn to the past, rather than the future, in their ongoing search for alternatives to the present, and you can find such merchandise on display in the Exhibit Hall.

Comic-Con as Life Support

Ironically, the least attended panels at Comic-Con are often those dealing with comics. Many people here love the content of comics, but many of them are not reading the comics themselves. At Comic-Con, both comics industry veterans and emerging talents often discuss their work in half-full rooms. And the massive waves of shoppers pushing their way through the Exhibit Hall often parted like the Red Sea when it came to the tables in Artists' Alley, which was really treated as Artists Ghetto. In 2011, many artists moved offsite, figuring they would see the same interested attendees and have more fun hanging out at a local tavern.

As a result of such apathy, the floppy monthly comic books my generation grew up reading may now be an endangered species. The major comics publishers have been absorbed by larger entertainment conglomerates--as Marvel is now a part of Disney and DC a part of Warner Bros.--which prop up the comics publishing ventures as a research and development wing to help the company incubate new media franchises. Cowboys and Aliens, the story goes, was published as a comic almost entirely because they wanted to see if it could build an audience before being turned into a feature film.

Yet many of the people who care about the survival of comics were gathered in San Diego, and there was lots of talk of "Comics without Borders." A few years ago, this phrase might have referred to the efforts of underground and alternative publishers to escape the constraints of the old Comics Code. Last year it referred to what happens after the bankruptcy of one of the two leading brick and mortar booksellers. Comics used to be available on spin racks in grocery and drug stores. In recent years, however, interested readers have had to seek them out, often stepping down into dark and dank basements where someone who looks and sounds like Comic Book Guy on The Simpsons comments on all of your purchase decisions. The publication of graphic novels and their distribution through chain bookstores brought comics out of hiding again, resulting especially in a dramatic increase of female readers. Now, so-called mainstream publishers (DC and Marvel) sell far fewer titles through comic book shops than the alternative publishers (such as DC's Vertigo offprint) sell through bookstores. And, curiously, Japanese manga outsell American comics by something like four to one in the U.S. market.

Everyone wanted to know what would happen to all of those casual and crossover readers now that Borders was closing operations. Some calmly suggested that they would simply cross the street to Barnes and Noble., Newly empowered, the Barnes and Noble chain is cutting more aggressive dealers with comics publishers. Meanwhile, DC and Marvel rolled out new strategies for increasing the availability of their titles for download on iPads and other digital platforms, a move which would increase their accessibility to fans but might further endanger the specialty stores for whom the big superhero titles constitute their bread and butter.

Meanwhile, there were gatherings of teachers and librarians who have been part of a larger movement to use comics to encourage young readers. The biggest growth in comics sales over the past few years has come from young adult or all ages titles, largely driven by sales to school and local libraries. Over the past few decades, the average age of the comics reader, much as with other print-based publications, was rising, threatening their industry's long-term viability. However, the success of comics in the library offers new hope for the next generation. So, if some seemed ready to hold a wake for comics, there were others who, mimicking Monty Python, protested that they were "not dead yet."

Comic-Con as Classroom

I had breakfast toward the end of the convention with a group of graduate students who were getting credit for attending and researching Comic-Con. This particular extension course has been run since 2007 by Matthew J. Smith from Wittenberg University in Springfield, Ohio, and attracts a diverse collection of students, all pursuing their own projects, using the con as their laboratory or field site. Kane Anderson, a stocky Performance Studies student with flaming red hair from U.C. Santa Barbara, , has spent the past two cons dressed in a range of skin-tight and brightly colored superhero costumes (Captain Marvel and Black Adam, mostly), trying to better understand what motivates the convention's cosplay. Melissa Miller, a Gothy gender studies and public communications student from Georgia State University, was back for a second year camping out with the "Twi-Moms," the mature Twilight fans, to better understand fandom's gender politics.

Throughout the event, I spotted different researchers interviewing people, taking field notes, and, in many cases, "going native" as they abandoned their research to chase after autographs. One of them was on a mighty quest to get Chris Evans to sign his Captain America shield; another was excited to get comic book uber-auteur Grant Morrison to fill out a questionnaire. One academic's artifact is another's swag. In fact, many of the young scholars were collecting gifts to carry back home to appease their restless thesis advisors.

Actually, some of their advisors were across the convention center attending events hosted by the Comic Arts Association, a professional organization for scholars researching and teaching about comics and graphic stories. Even as the comics industry is sputtering, there has been a spurt in college-level comic studies courses, much as previous generations had taken subjects in film appreciation. Inside this space, the big debates focused on whether comics studies should become its own discipline or whether comics-focused research should be integrated across everything from anthropology to

art history, from psychology to media studies. This track of academic programming attracted not only faculty and students but creators eager to think about their industry from a different perspective and fans hoping to learn more about the medium's history and aesthetics.

Comic-Con as Ritual

For the past few years, the formal programming at Comic-Con has ended with a sing-along screening of the musical episode from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, "Once More, With Feeling." However diverse they may be on other levels, a high percentage of Comic-Con attendees are fans of the works of Joss Whedon--Buffy, Angel, Firefly/Serenity, Dollhouse, Doctor Horrible's Singalong Blog, and the forthcoming Avengers movie. And Whedon, as well as others from his casts and crews, was highly visible throughout the convention. Consider all of the Buffy alum, in particular, who were prominently involved in the event: Sarah Michelle Gellar (Buffy) was there promoting her new CBS series, Ringers; Anthony Head (Giles) was speaking on the Merlin panel and trying to lend his support to Grimm; Nathan Fillion (Caleb), now the star of Castle, was there talking one-on-one with his fans; Felicia Day (Vi) was showcasing the fifth season of her web-series, The Guild; and Seth Green (Oz) dropped by to talk up Robot Chicken. David Boreanaz (Angel) was supposed to be here, but the Bones panel got canceled. And Nicholas Brendon (Xander) came out in front of the sing-along screening and tried to remember the words to the song Anya and Xander sing in the episode. Think of this group as the Buffy diaspora.

In this context, "Once More, With Feeling" has attained near-mythic status--not only because of its genre-bending musical numbers but because it represents the last moment when the "Scooby Gang" was more or less together before the series "jumped the shark," according to many of its fans (myself among them). When Dawn, Buffy's kid sister, introduced the plot elements which would lead to the community's disintegration in the episode, she was booed. Everyone knew what was coming, but we all wanted to forestall it a few minutes more.

Many fan favorites center around themes of friendship, whether bonds between partners or a more expansive community fighting to save the universe. Fans use such stories to reflect on their own social connections, the bonds that bring them together as friends and as part of a subcultural community. For many of us, fandom is one of those places where "it gets better," where we find others who share our values and don't make fun of our passions.

We can share some of these same experiences now, year round, in cyberspace. But Comic-Con is the place where communities come together face-to-face, and thus anchor their relationships for the coming year. As Buffy ended, with friends going their separate ways, and as people filed out of the doors of the San Diego Convention Center, I felt a lump in my throat. But I knew that most of us would be back next year, "once more, with feeling."

Comic-Con is a microcosm of the dramatic changes transforming the U.S. entertainment industry.

As media options proliferate, attention is fragmenting and audience loyalty is declining. The entertainment industry depends on its fans like never before. As social media allows fans to connect with each other and actively spread the word about their favorites, fans are exerting an unprecedented impact on decisions regarding which films to finance and which series to put on the air. As more and more stories are being told across media platforms, Comic-Con is the crossroads among entertainment sectors. As comics publishing is struggling to survive, here is where its future will be determined. And, as Comic-Con's own population diversifies to include more women and minorities, this gathering becomes a vehicle through which they lobby for greater diversity within mainstream media.

That all of this takes place in such a giddy atmosphere, full of carnivalesque costumes and grand spectacle, only lubricates the social relations among these groups, making it easier to shed old roles and embrace new relationships. For those five days, the center of the U.S. entertainment industry is not Hollywood, but a few hundred miles south in San Diego.